When the flag of the newly independent Ghana was raised against the night sky of Accra 63 years ago, the whole world was looking on. It was the first country in sub-Saharan Africa to gain its independence from colonial rule. Other Africans watched with trepidation given that so much hung on its success. Other, mainly Western countries, watched with curiosity, or, in the case of colonial powers, with concern.

Prime Minister Kwame Nkrumah was about to embark on a new political experiment.

The leader of Ghana envisioned the complete transformation of the continent, starting with his own country. He declared that “the voice of the new African in the world” was going to be heard for the first time. He and his mentor and political adviser, Trinidadian Pan-Africanist George Padmore , crafted an ideology based on black nationalism, pan-Africanism, Marxism, nonviolence and “positive non-alignment” or “positive neutrality”. After 1960 the ideology would be called Nkrumaism.

Nkrumaism called for the liberation of the continent through mass nationalist movements without reference to ethnicities, tribes and religions, and for unity of the newly liberated nations under one flag. It also called for the development of the continent through a socialist planned economy.

Finally, the ideology prescribed the unity of the continent under one socialist government as the only means to defend African independence from colonialism and neo-colonialism.

The influence of Nkrumaism has been the subject of a great deal of analysis and debate. I have studied the way scholars have written about Nkrumah’s years in power, focusing on his ideology and foreign policy, and have identified three main periods in the literature. The three periods into which I divide the scholarly debates coincide with major political changes in Ghana and in Africa as a whole. By analysing these changes it is possible to make sense of a huge literary production on Nkrumah’s ideology and foreign policy.

Why it matters

The government of Nkrumah in Ghana (1957-1966) is undoubtedly one of the most controversial in the history of modern Africa. For nine years, the “Osagyefo” (“the redeemer” in the Akan language) tried to transform Ghana into a Nkrumaist and Pan-African nation and simultaneously tried to export his ideas to the rest of the continent. His goal was to find enough followers among African nationalists to form the basis for a continental government, a future United States of Africa.

He based the foreign policy of Ghana on the achievement of African unity and the support of other liberation movements.

For many Ghanaians Nkrumah’s rule represented failed dreams and promises, for others a sound project of development and a promise of greatness abruptly ended by foreign forces.

For many, his ideas were fascinating back then and still are. For others, pan-Africanism was, at best an unrealistic dream, and at worst an attempt by Nkrumah to become a dictator.

Such a dichotomy of views has been going on for decades. Scholars have long debated the figure of Nkrumah and his significance for Ghana and Africa as a whole.

The work I have done on Nkrumah is important for any student or scholar who is interested in the man. This is particularly the case given that interest in this crucial figure of African history has been growing in the past three decades.

Analysing the debates

The first period I identified coincides with Nkrumah’s political life (1945-1972). During these years, pro- and anti-Nkrumah parties clashed vigorously. Several scholars, intellectuals and politicians labelled the Ghanaian leader as one of the biggest failures of the post-colonial African leadership. Others fed his myth to the point of glorifying his martyrdom at the hands of neo-colonialists.

Behind all these analyses was the shadow of Cold War politics. Two different visions of Africa’s post-colonial future, one defined as “Afro-optimist” and the other “Afro-pessimist”, were influential too. Was Nkrumah’s project a failure or was it a hope for the continent’s development and unity?

With the death of Nkrumah (1972) a second period began (1970s-1980s). Numerous studies and memoirs began to shed new light on his life, convictions and policies. A more detached analysis of the facts began to emerge. Still, limitations on the access to primary sources, due mainly to the fact that most were destroyed, lost or seized during the coup of 1966, as well as the influence of “Afro-pessimism” in this period, negatively affected the debate.

For a long time, as highlighted by the political scholar Ali Mazrui, this theme was particularly sensitive in Ghana, where it limited the debate. Something, however, began to change during the 1980s. Author and academic David Rooney wrote in 1988 that “the perspective is shifting”. Finally, it became possible again to discuss Nkrumah in Ghana in a more detached and rigorous manner.

Two symbolic events certified this passage. The first was the publication, in 1991, of the papers of the symposium “The life and work of Kwame Nkrumah”, held in Ghana in 1985. The second was the construction of the Kwame Nkrumah Mausoleum in Accra in 1992. With this move, the then president of Ghana, JJ Rawlings, transformed Nkrumah into the father of the nation.

Globally, the end of the Cold War led to a reconsideration of the past decades. The historical debate became less and less influenced by Cold War ideologies and worldviews.

In the third period, the retrieval of previously inaccessible documents was another factor that allowed for a more scientific analysis of Nkrumah’s times. New perspectives have been explored.

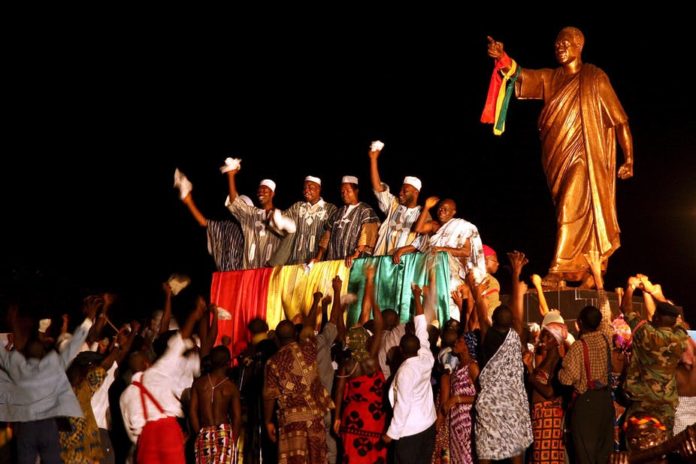

Outside academia, too, Nkrumah is again internationally recognised as positively influential. His name is still widely evoked by protest movements, political parties and politicians, either as just an abstract symbol of freedom and pan-Africanism or as the bearer of a concrete proposal for a radical change in African politics.

The debate on Nkrumah and his pan-African ideology is far from being exhausted. In order to fully understand the man and his ideas, it is important to be aware of how this important figure has been viewed over the years.

Read more: Kwame Nkrumah: why, every now and then, his legacy is questioned

Matteo Grilli, Post doctoral researcher, University of the Free State

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.