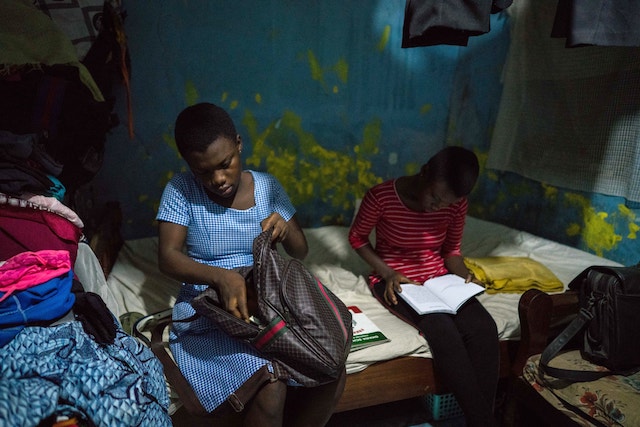

At dawn on a recent Tuesday, 18-year-old Jane Newornu pulled on her blue gingham school uniform, stuffed her books into her knapsack and grabbed a banana as she ran off to school.

Her twin sister, Jennifer, still in her pajamas, watched with a pang of envy. Instead of going to class, Jennifer was staying home from school on a two-month hiatus mandated by the government. The twins, like all high school students in Ghana, now must take turns.

The problem is the result of the tumultuous rollout of a new government program, intended to expand access to free secondary education. When President Nana Akufo-Addo took office in 2017, he made good on one of his chief campaign promises: tuition-free high school for all.

It was part of a broader effort to make Ghana internationally competitive in educational standards, agriculture, tourism and more. But the program has proved so popular — 430,000 students are enrolled this school year, up from 308,000 in 2016, according to the education ministry — that demand has overwhelmed capacity.

“We want parents to see education as what can transform this nation,” said Yaw Osei Adutwum, deputy minister for education. “And therefore, even if they have to make some sacrifices, it’s worth it.”

Staggering students has been used in many countries to reduce overcrowding, including Japan and Australia. Ghana’s idea was inspired by California, according to Dr. Adutwum, who ran a network of charter schools before being appointed deputy education minister in 2017. Starting in the 1970s, some school districts in California adopted a multitrack system after a boom in the student population.

While elementary and middle school are compulsory and free in some parts of West Africa, tuition-free high school is rare. A handful of countries, like Burkina Faso, offer free high school for poor students if they keep their grades up. Last year, Sierra Leone also introduced free high school for 1.1 million students. But the rollout was fraught: some children were turned away because of lack of space, according to news reports.

Under what Ghana’s government calls a two-track system, some children go to school while others take a break. It has succeeded in wedging more students into classrooms. Supporters say it is a temporary solution while more teachers are hired and schools are built and put it down to growing pains.

But many parents, watching their children sit idle for two months, are furious. They now believe they were sold a bill of goods by a government that made a promise it couldn’t keep. If sidelined children slip behind in their studies, some adults and students say, then free school comes at too high a cost.

“I’m not happy with this system,” Jennifer Newornu said as her sister sashayed out the door to class while she stayed in bed. “I stay home for too long. It’s actually boring. And not helpful.”

But the government is unwavering in its support of the new system, saying it delivers adequate education to more children. Before the program, 67 percent of children who attended elementary went on to secondary school. But since the launch of the new program, it climbed to 83 percent in 2018, according to the ministry of education.

In Ghana, elementary and middle school has been free and compulsory since 1995, with a 90 percent enrollment rate. But high school, though government-run, required tuition.

Government boarding schools cost about $289 per school year, day school about $120, according to government data. These are significant costs in a country where the average annual per capita income is about $1,900, according to the World Bank.

The program has only been implemented so far in high schools with high demand, but the government expects more to be added as enrollment increases. Sixty percent of public high schools in Ghana are boarding schools, which are included in the free tuition program.

Free high school is one of a number of reforms under President Akufo-Addo’s ambitious overhaul of Ghana’s entire education system, officials say. Student performance will be evaluated yearly, rather than in one all-important final exam before graduation.

The country’s memorization-heavy curriculum is being updated to focus more on critical thinking and comprehension. Educational support for students who struggle academically, once paid for by parents, is now free.

“The system that we inherited, everything about it, was not about the 21st Century,” said Dr. Adutwum. “When it comes to international competitiveness, we are not there, and we want to be there.”

He said that waiting to build new schools to fit all the new students would have delayed free high school for thousands of children for years. Implementing the program, which covers fees, course books and uniforms for each child, cost about $74 million in its first year, according to the education ministry.

The government says it plans to build more schools and eliminate the staggered system in five to seven years. But educators are skeptical.

They say free tuition is meaningless without more teachers and materials, and major upgrades to the country’s crumbling schools. Without that, they say, students will continue to struggle.

When Jane arrived at Salem Senior High School in her gingham uniform, students were playing volleyball outside the headmaster’s office. Every seat in her first period class — home economics — was occupied. Teachers said they have worked continuously for several semesters without taking a vacation day.

The headmaster, Rev. Anthony Odame Lartey, said of the free school program, “It is allowing access. A lot of children have been left behind without this system.

“But we need facilities, we need equipment, we need teaching materials,” he added. “I wish that money would be pushed into teaching and learning.”

With so many students out of class, companies have popped up offering at-home tutoring and vacation classes. With names like “Intellectuals Academy,” they advertise on television and billboards. Education officials dismiss the need for such extracurricular education, regarding it as fearmongering designed to sell sessions with a tutor.

But Gilbert Nartey, a real estate agent from Accra, believes that such extra lessons are necessary for his nephew, whom he is raising, to keep him up to speed and out of trouble.

“He is a child, he needs to be always engaged. When you leave him or her for two or three months unattended to, they will develop certain habits,” said Mr. Nartey, who is 60.

He said he spends about $100 on tutoring each month that his nephew is out of school. Added up, it is more than he would have spent on tuition. Parents who cannot afford the sessions fear their children will be left behind academically.

“The idea is fantastic, but the implementation is worthless,” Mr. Nartey said of the new school initiative.

The twins’ father, James Newornu credits the president’s free school program with allowing his girls to attend high school at all. He recently lost his job as a taxi driver and said he could not have afforded to pay school fees.

But watching Jennifer scroll through her phone, or hang out with other stalled high schoolers during her break, he has grown concerned. To parents like him who cannot afford tutors, it is just another way that the new system still fails to close the gap between rich and poor.

“This system isn’t helping,” he said. “They tend to forget what they’ve been taught.”

For the past two months, Patricia Dorgbe, 17, has worked at her older sister’s clothing stall on Oxford Road in Accra while she waits her turn to go back to school. On a recent Friday morning, she watched listlessly, dressed in her school uniform, as her classmates walked past her booth on their way to school.

On Monday, it would at last be her turn to go back to class.

“I’m worried. We are going back to school, but it will be difficult for us, those sitting around at home,” said Patricia, who dreams of becoming a nurse. “But I have to go ahead and try my best, so that I will be able to achieve whatever I want to.”